by Scott Martin Photography | Jul 14, 2014 | Birds, Blog, Loons, Shore Birds & Waterfowl, Wildlife

In North America there are seven species of Grebes, however this post will focus on the Red-necked Grebe, which is a medium to large sized bird that frequents fresh water marshes and lakes from the north-west (Alaska & the Yukon) extending southwards to Texas. It is rarely found east of Ontario.

The Red-necked Grebe is a rather nondescript grey bird during the winter months, however transforms into the beautiful bird in this post when it adopts its breeding plumage, including its red neck, white face and black crown with its characteristic tufts.

Grebes typically nest on floating beds of vegetation which allows for protection from the usual land based predators. Like Loons, Grebes are awkward taking flight and ‘run’ along the water for a long distance before acquiring the speed required to take flight. As a result of this you don’t often see Red-necked Grebes in flight other than during migration. Also similar to the Loon, the Grebe’s legs are positioned far back on its body making it very immobile on land but adept in the water. The Grebe dives when faced with a threat as opposed to taking flight. This next image show an adult on the floating nest (in breeding plumage both sexes appear the same so differentiation is very difficult, although the male is usually the heavier of the two sexes).

Red-necked Grebes lay two to six eggs which enjoy shared incubation for 20-23 days before hatching. This family had four young ones making for a busy time of feeding. The biggest threat to the young chicks are fish (particularly pike and muskie) and snapping turtles and for this reason, along with the desire to keep warm and comfortable, they spend the first few days of life snuggling on the backs of the parents. It is always a treat to see these young families and watch the young jostle with each other to get the favoured position on mom or dad’s back.

The choice position cuddled at the base of a parent’s neck is only available to one, but perhaps they take turns! Young birds grow very rapidly and Grebes are no exception, so the opportunity to see them on the backs of the parents only lasts for a few days. In just a few months they must be big enough and strong enough to migrate south for the winter. Interestingly, Grebes migrate mostly at night.

The little sentinel, learning to be a keen observer of the surroundings. Observational skill is essential for survival and although the Grebe reduces land based predator threats by nesting on the water, other birds (hawks and gulls) pose danger as do many other aquatic adversaries (fish, snakes & turtles). Grebes are typically very quiet however when threatened do make a series of loud and unusual screeches & squawks.

The chicks have very distinctive black and white banding patterns on their head and necks which give them a little zebra like appearance. This next shot captures the unique beauty of the young birds head.

Red-necked Grebes consume mostly invertebrates including insects, molluscs, dragonflies, beetles and crayfish and they also eat fish. The Grebes also have a very peculiar item on their menu; they regularly eat their own feathers and in fact start feeding feathers to the young when they are only a few days old. The feathers remain in the stomach and tend to partially decompose into a soft amorphous mass. It is not known what the purpose of the feathers in the stomach is, although it has been suggested that they form a filter of sorts to prevent ingested bones from damaging the digestive tract.

While my good friend Arni and I were photographing the Grebes pictured in this post, we had the privilege of watching the young chicks being fed numerous times. The challenge was to get a great feeding shot with everybody looking at the approaching meal. Fortunately all four of the young cooperated at least for the split second required to get this shot. This shot is also humorous in that Dad is being overly optimistic in just how big of a fish the young ones could handle and the weight of this meal caused it to be dropped as soon as it was handed over. No problem though as the parent immediately returned with a smaller fry for the youngsters.

I was hopeful to photograph a Grebe chick on the back of a parent while swimming away from the nest, however this was not be. The next two images were as close as we were able to get, but that’s the beauty of bird photography, no matter how many great shots you’ve taken there is always a better one to be had next time. So we keep on looking for that ‘perfect’ yet elusive shot.

.

The Red-necked Grebe was an interesting bird to observe and photograph. They are also very photogenic as this concluding image demonstrates.

A couple of interesting facts regarding the Red-necked Grebe is that its feet are lobed rather than webbed and a group of Grebes together on the water are referred to as a ‘water dance’ of Grebes.

All of the images in today’s post were taken hand-held with a Canon 5D Mk III and EF 500 mm f4 L IS lens. Normally I use a monopod to support the weight of the lens, however as all of the images were taken while lying down to get a more desirable low angle, support for the lens was not available.

by Scott Martin Photography | May 13, 2014 | Birds, Blog, Shore Birds & Waterfowl, Song Birds, Sparrows

Todays post will only contain three different birds, however all three have stories and images that I trust you will enjoy.

The Painted Bunting is arguably the most colourful North American bird with its vibrant red, yellow, blue and green colours. It is a relatively common bird found in South-Central and South Eastern ares of the United Sates and into most of Central America. It’s a bird that is not often seen as it prefers the cover provided by thickets and underbrush although it does frequent back yard feeders for seed. It is such beautiful bird it is sometimes trapped and sold in Mexico & the Bahamas as a caged bird. Fortunately this practice is illegal in the United rates. For the last few years Painted Bunting have wintered on Merritt Island and these next two images of a male were taken there in March of this year.

.

The All-American couple with a feeder to match!

You can see other Painted Bunting images in the Sparrows, Grosbeaks, Buntings & Finches Gallery.

Approximately thirty miles south of Merritt Island you can find the Viera Wetlands which is a favourite location for bird photographers while visiting the Space Coast of Florida. The Viera Wetlands are home to hundreds of species of birds and the topography of the area makes it possible to get quite close to the birds if you are patient. Of the many Heron species, the Green Heron is one of my favourites. Although not a large bird its feather colouring and detail is impressive. They tend to stay in heavy reed cover at the edges of swamps and marshes where they stealthily hunt small minnows and fry that unknowingly swim under their perch. This year it was a pleasure to see a Green Heron fishing and a pleasant surprise to be able to photograph the action. Deb & I watched this particular bird move throughout the reeds for about thirty minutes until we actually saw him capture his prey.

Posing for the camera!

Intently looking for lunch.

Having a closer look.

Taking a stab at it.

Success!

The last bird in today’s post is the Black Skimmer, a common bird with a most uncommon beak. In fact, it is like none other bird in North America as the lower mandible is about half to three-quarters of an inch longer than its upper mandible. A most unique design that makes digging for worms or picking berries next to impossible, yet is perfectly designed to do what the Black Skimmer was made to do….skim along over the calm water with the extended lower jaw just below the water’s surface and extracting food from the water as it travels up into the mouth of the bird before exiting in a stream of water from the base of the mandible.

Although Deb & I have watched skimmers skim in the past, it was not until this year that we were able to take some decent photographs of the action. So it was a great experience that was only heightened by the fact that they were about ten years in the making!

X marks the spot.

.

.

This last skimming image was taken in the rain and in a different location that provided a dark back ground, not ideal for isolating the Black Skimmer from the back ground but nevertheless creates an interesting result.

A number of other Black Skimmer images, including close up pictures of the unique mandible and normal in flight images can be seen in the Gulls, Terns & Skimmers Gallery.

All of the images in today’s post were taken with the Canon 5D MK III and EF 500 f4 L IS lens, sometimes with the 1.4x TC attached (allowing the 500mm lens to function as a 700mm lens).

This brings our March Break 2014 bird photography to a close and we will return to our tour of Europe for the next few posts. In the mean time we are heading into another time of year when there are an abundance of great looking birds fairly close by, including many species of Warblers that are passing through the Oshawa area on their way north country for nesting and breeding. Hopefully we will be able to have a Warbler Blog post this spring!

by Scott Martin Photography | Apr 27, 2014 | Birds, Blog, Raptors, Shore Birds & Waterfowl, Woodpeckers

Every year we look forward to spending time in Florida over the March Break. Our typical schedule is to spend three or four days on the Atlantic coast in Melbourne and then a week at our timeshare in Kissimmee. These locations provide easy access to our favourite bird photography sites which include the Viera Wetlands, Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, and Joe Overstreet to name a few. March is a great time for bird photography as many of the birds are in their annual breeding plumage and the winter migrants have not yet left for their flights north. This winter we were able to photograph a number of different birds, and although no new species were captured we did manage to photograph Black Skimmers skimming, something we’d been trying to do for many years. Todays post is a compilation of the birds we saw this March, with the exception of the skimmers which will be part of another post.

Over the years we’ve photographed many Roseate Spoonbills, but always in flight or perched in trees. This was the first time we were able to get close to them on the ground (Blackpoint Trail, Merritt Island).

.

Great Blue Heron Family (Viera Wetlands).

.

.

.

.

.

Another Viera favourite is the Limpkin, which is one of two birds that are locally endangered in Florida that eat Apple Snails almost exclusively. This first image catches the Limpkin shaking the rain drops off.

.

The other Apple Snail enjoying, locally endangered Florida bird, is the Snail Kite. This one was seen at Joe Overstreet.

.

Other Snail Kite images from past years can be found in the Hawks, Falcons & Kites Gallery. While at Joe Overstreet we found this juvenile Yellow-bellied Sapsucker.

.

Another common Florida Woodpecker is the Red-bellied Woodpecker (Merritt Island).

The American Bittern is a large bird that is not easily seen as it blends so well into its chosen surroundings where they extend their necks to parallel the grass, which along with their striated coloration makes them almost invisible (Viera Wetlands).

.

A bird that is seemingly never inconspicuous is the Anhinga, which because it lacks oil secreting glands to waterproof its feathers, must dry out in the sun after being in the water (Viera Wetlands).

America’s official bird, the Bald Eagle is a regular patroller of the Viera Wetlands airspace.

One of the cutest birds in Viera was this little Pied-billed Grebe.

If the Grebe is a bird everyone likes, perhaps the other end of the spectrum belongs to the gulls, which rarely garner much attention, although when one flies overhead with a big fish, you just have to take the shot (Joe Overstreet).

These Terns were photographed at Viera and Joe Overstreet.

.

.

To close this post, something completely different; the Florida Soft Shelled Turtle (Viera Wetlands). It is the largest soft shelled turtle in North America and is very fast on both land and in the water as evidenced by the webbed feet visible in the picture.

I trust you’ve enjoyed this rather eclectic grouping of some of the birds we enjoyed seeing in Florida this year. In the next post we will feature three birds which provided some memorable photographic opportunities, the Painted Bunting, Little Green Heron and Black Skimmer.

by Scott Martin Photography | Mar 3, 2014 | Birds, Blog, Educational, Raptors, Shore Birds & Waterfowl, Wildlife

This winter has been unusually long and cold with our province blanketed in snow to depths that I can’t recall since growing up in the Ottawa Valley. Fortunately it has also been a pretty good winter for bird photography, especially regarding Snowy Owls for which this year has been an irruption year. An irruption year occurs infrequently and although there are different theories as to exactly what causes a particular species of bird to head farther south in greater numbers than usual, it most likely revolves around competition for food. In winters when food supplies are scarce or years that bird populations are large, the competition for food forces the disadvantaged (the young, very old or infirm) south in search of more easily obtained food. This is why Snowy Owls found significantly south of their normal range are usually young first year birds. After wintering farther south than normal and eating well, the owls head back to the Arctic in February or March for the next nesting season. The Snowy Owl irruption experienced this year has been the largest in 40-50 years and a Snowy Owl actually made it to Jacksonville Florida, which is incredible for a non migratory Arctic bird! When Snowy Owls are displaced southward they seek areas to stay that remind them of the tundra they are accustomed to, so you often find them in open areas such as farmers fields.

Their predilection for farmer’s fields results in the classic images we see of Snowy Owls perched on fence posts.

Although not the biggest or heaviest owl, the Snowy is still an impressive bird about 2.5′ high with a wingspan of five feet and weighing up to six pounds. Only in flight can you get an appreciation for their wingspan.

Deb and I were photographing a Snowy Owl last month when a snow squall moved through the area and presented us with the opportunity to get a unique image that I hope illustrates the type of environment the Snowy Owl is used to in the high Arctic.

The winter months in Ontario are also a great time to see a number of northern diving ducks which winter on the Great Lakes. In fact the introduction of Zebra Mussels in 1988 to Lake St. Claire and Lake Erie from a European freighter and their subsequent infestation of the Great Lakes (particularly Erie & Ontario) has provided a dubious but plentiful food source for the ducks. Consequently in recent years we have seen more varieties of ducks as they change their historic migration patterns to include the Great Lakes and the Zebra Mussel buffet they provide.

On a recent tour of Southern Ontario looking for winter owls and ducks with my good friend Arni, we were able see a number of different duck species as well as four different owls species. Arni is a birder and photographer second to none and you will enjoy following this link to his website. These next images of ducks were taken on our tour and although it was a dreary day the poor light did not stop Arni and me from enjoying both the birding and the photography as well.

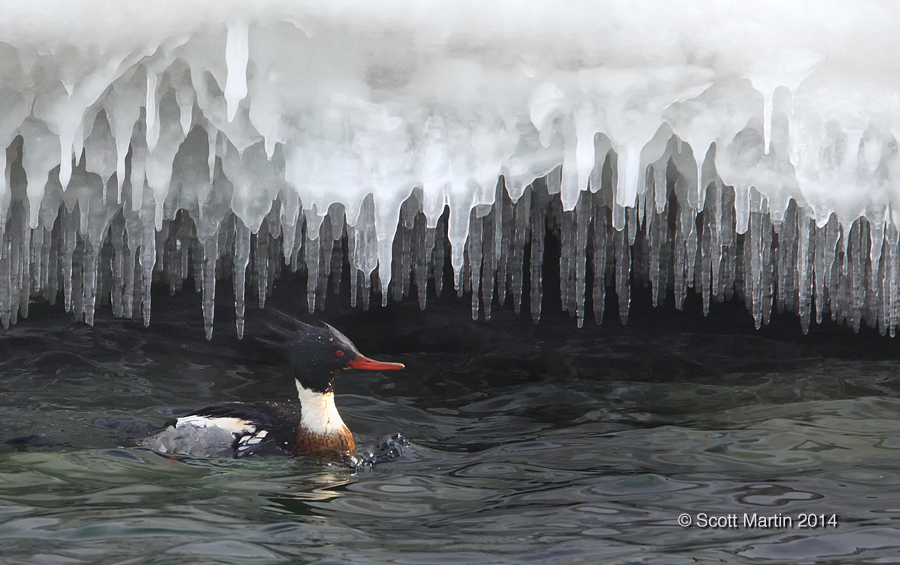

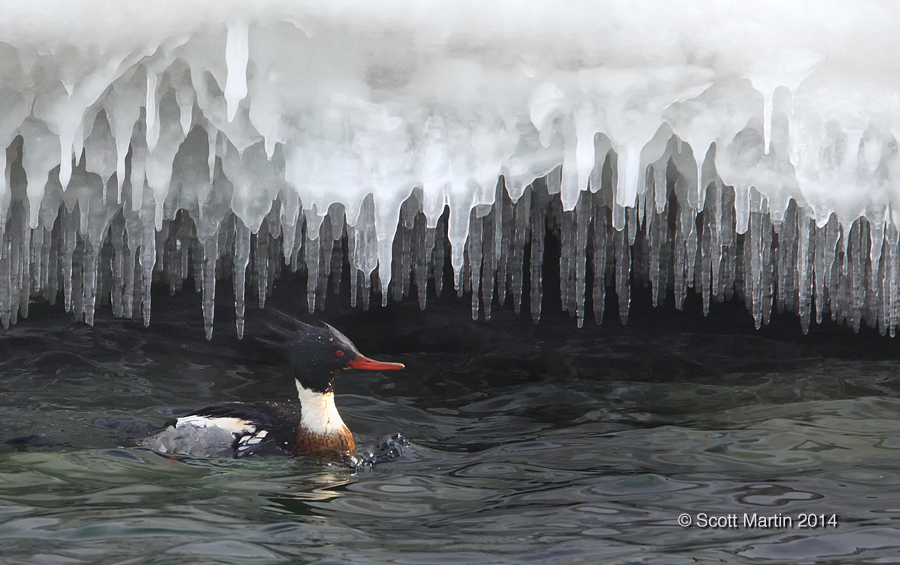

First up is the Red Breasted Merganser, the rarest of the three Mergansers in North America, and a new bird for me to photograph. If you want to see the other two Merganser species (Common Merganser and Hooded Merganser), they can be found in the Waterfowl Gallery.

Baby it cold outside!

.

This next image is of Red-headed ducks, another relatively new and unusual visitor to the Great Lakes to feast on the Zebra Mussel. The Red-headed duck is an interesting species as it never builds its own nest, choosing instead to lay its eggs in the nests of other duck species and even in the nests of American Bitterns and Northern Harriers. Apparently they aren’t into parenting!

The White-winged Scoter is another Arctic breeding duck that is found through North America, Europe and Asia. It heads south in the winter months and their numbers have been increasing on the Great Lakes over the past few years. They are a large dark brown to black bird with distinctive white markings around the eyes and speculum. The next two pictures are of the White-winged Scoter, the male first followed by the female and both with a clump of Zebra Mussels.

.

Since the inadvertent introduction of Zebra Mussels to the Great Lakes, they have overtaken Lake St. Claire, Erie and Ontario, largely due to their prolific reproduction with relatively few predators eating into their numbers. A Zebra Mussel has a life span of approximately five years and females begin having young at about six weeks of age, producing one million offspring annually. The crayfish, one of the mussel’s main predators, consumes about 40,000 per year. The Zebra Mussel filters approximately one gallon of water every day, removing nutrients for itself. Unfortunately the toxins in the water, of which there are many, accumulate in the mussel and there in lies the problem for the birds who consume the muscles and with them the toxins and contaminants from the lakes, and in a concentrated form. The health effects on the birds is not yet known, however it is a huge concern to conservationists and researchers who are investigating the effects of the muscles on birds. It is already suspected that avian botulism is transferred via the Zebra Mussel and this kills many birds annually.

Shifting gears back to owls, the first of four owl species Arni and I saw was the Eastern Screech Owl, which was a new species for me to photograph. The Eastern Screech Owl is a strictly nocturnal bird that hunts at night and then finds its roost in a tree cavity where it spends the daylight hours sleeping. They are a small bird about 10″ high with a wingspan of 18-24″. Most Eastern Screech Owls are grey in colour, however about 10% of these owls are a rufus or red morph and it was a pleasure for us to have found this rarer colour of the Eastern Screech Owl.

After leaving the Screech Owl we were able to find a Snowy Owl however he was too far away to get any blog worthy images of so we left and arrived at another location where we found a Short-eared Owl hunting over a large area around a quarry. Although we set up out tripods and gear, the Short-eared Owl didn’t fly close by, so as with the Snowy Owl, we struck out getting any shots. The disappointment was short-lived as after arriving at a conservation area on the shores of Lake Ontario we found a large coniferous tree that was home for the day to six Long-eared Owls. It was the largest number of owls I’d ever seen in the same tree.

The Long-eared Owl is a slender owl with long ears, large bright yellow eyes and huge eye discs that give it a characteristic look that is hard to miss.

It was also a pleasant surprise to catch one in flight.

Many photographers put their camera gear away for the winter, but as long as you dress for the occasion and make sure your batteries are fully charged, cold weather photography is a lot of fun and often affords the pleasure of seeing birds that you simply can not see in Ontario at any other time of the year.

We’ve been privileged this winter to also have photographed two other species of owl, the Great Gray Owl which the world’s largest owl and the Short-eared Owl which is arguably the prettiest of the owls. They will form the subject matter for the next two blog posts before retuning to our European tour.

by Scott Martin Photography | Jan 4, 2014 | Birds, Blog, Shore Birds & Waterfowl, Wildlife

The Mandarin Duck is a local rarity and a bird I had never seen before in the wild so when a single drake showed up in Whitby it created quite a flurry of interest.

The Mandarin Duck is an East Asian perching duck found primarily in Russia, China and Japan. It is a medium sized duck and is closely related to the North American Wood Duck and is similar in that they both nest in empty tree cavities, sometimes as high as thirty feet above the ground. After the chicks are born the mother pushes them out of the tree and then leads them off to the nearest body of water. Mandarin Ducks are among the most beautiful and colourful ducks as the following pictures shows.

When shooting birds on the ground it is important to get the camera at their level in order to achieve the best results. The above shot was taken while lying down on the ground resting the 70-200mm lens on the palm of my hand. The next image was taken from a sitting/kneeling position to show the colour ranges and feathers detail on the dorsal aspect of the bird. Although the shot accomplishes the purpose you can clearly see the better perspective of the first image. So next time you are photographing anything on the ground, don’t forget to lie down and get the job done right!

Although there are a few feral colonies of Mandarin Ducks in North America, they were probably created by the escape of bids from captive collections (i.e., zoos). It is unlikely they are a result of misplaced migration from East Asia. In all probability the Mandarin drake that arrived in Whitby is an escaped captive bird.

The only open water for this duck is a pool created by the fast flowing water from a couple of late drainage pipes that is only about thirty feet in diameter. This little Mandarin Duck shares the small pool with about a hundred Mallard ducks and a few Canada Geese so it was very difficult to get any images of the Mandarin alone in the water. The following three are the best I could do.

Frolicking

Water off a duck’s back!

When photographing wildlife it is always best to take lots of exposures when the target is in your viewfinder as the spontaneous nature of wild animals often presents some interesting even humorous actions. This is completely different from landscape photography where the subject doesn’t move and you can invest as much time as necessary to plan, compose and execute the ‘perfect’ single image and then move on to the next shot.

Spontaneous ‘snapshots’ don’t have to be perfectly composed with tack sharp focus (although it helps) as long as the story the image tells or the smile that it creates is the overarching result of the photograph. Here are a couple of such snapshots obtained while photographing the Mandarin Duck this week. Although not typical images for posting on photography blog designed to showcase great photography, I do trust you enjoy them and they give you a smile.

Stepping out with the big boys! (this does provide a good perspective for appreciating the size of the Mandarin Duck).

Where angels fear to tread.

The first two images in this post were taken handheld with the 1D Mk III and 70-200mm/2.8, while the three shots of the duck on the water were using the 5D Mk III and 500mm/4, again handheld. Although these body/lens combinations may seem odd, some thought went into them. The 1D body has a crop factor of 1.3 meaning that a 100mm lens functions like a 100 x 1.3 = 130mm lens when attached to the crop body. So a crop body lengthens the effective reach of the lens compared to the same lens placed on a full frame camera like the 5D. Knowing that it was possible to get relatively close to the ducks, putting the crop body on the smaller lens and the full frame body on the longer lens created the optimal effective focal ranges for getting the best pics of the Mandarin Duck.

by Scott Martin Photography | Apr 23, 2013 | Birds, Blog, Shore Birds & Waterfowl

The Belted Kingfisher is one of approximately one hundred species of Kingfishers world-wide however it the only Kingfisher found commonly throughout the entire North American continent. It is an easily recognizable bird owing to its relatively large head and bill along with a shaggy looking crest. One of few birds that nests underground where it lives in a burrow dug out of the side of a river bank. Interestingly, it always burrows in an uphill direction such that in the event of flooding an air pocket is trapped at the top of the burrow allowing it to survive until the flood waters recede. Kingfisher tunnels have been recorded up to eight feet in length. Its diet consists of many things including crayfish, amphibians, small mammals, birds and even berries however it is primarily a fish specialist. The Belted Kingfisher perches above streams or hovers in flight above the water looking for fish to dive for.

For bird photographers, the Belted Kingfisher often appears on the top of what is euphemistically known as the nemesis list, or list of birds that has generated the most difficulty, frustration and angst to photograph. Although Belted Kingfishers are very common along rivers and streams in North America, they tend to be very skittish and don’t allow people close access, thus making them difficult to photograph. My good friend and fellow bird photographer Arni Stinnissen and I have enjoyed a friendly rivalry over the past few years to capture some quality images of Kingfishers, and most certainly Arni’s results have been far superior to mine as you can see in his Kingfisher Gallery. Last month, while vacationing in Florida, Deb & I had the opportunity to watch a Belted Kingfisher fish for about thirty seconds approximately one hundred feet from where we were standing on the shore of Lake Kissimmee. Fortunately I was able to get a few shots of the Belted Kingfisher diving. Although the distance from the bird precluded the quality of images one would like, they do capture the diving behaviour of the Kingfisher which is something rather unusual and I trust you will enjoy seeing.

The Kingfisher was hunting along the shoreline of the lake and as there were no perches in the area, she would hover about thirty feet above the water looking for fish.

The female Belted Kingfisher is slightly larger than the male and is also one of the few species of bird where the female is more colourful than the male. The female is easily differentiated from the male by the rufus stripe across the chest below the slate blue belt that is found in both sexes.

Once a fish is spotted the Kingfisher dives very quickly striking the water at a high rate of speed propelling it well below the surface.

Note the clean lines of the entry zone, which will help make the next few slides make more sense as they record the Kingfisher launching itself out of the water at the end of its dive. Although I’ve seen Kingfishers dive many times before I had no idea how they launched themselves out of the water so the following images proved very educational. The next slide shows the appearance of the tail and wingtips as the Kingfisher prepares to use a strong wing beat to propel her body straight up out of the water. You can tell this is an exit shot by the waves around the impact zone and the seaweed in the air above the bird caused by the prior impact.

The energy expended to launch the bird vertically from the water must quickly exhaust the bird, so I doubt they can make many dives without a rest.

The vertical distance required must be high enough for the bird to take flight.

And off she goes, in this instance without any food.

.

.

.

It was a blessing to be standing in the right place at the right time to record this Belted Kingfisher diving and as a result learn a little about how they ‘eject’ themselves from the water after a dive. It was also a pleasure to ‘kind of’ cross a longstanding bird off the nemesis list, not completely though, as I still need to get some print worthy images of this intriguing bird.

The above sequence was taken using a Canon 5D MkIII with a 500 mm f/4 lens, not a set-up typically used for birds in flight, however the 5D autofocus seemed to track the bird well.

Follow Scott Martin Photography